Skill Differences and Lifestyle Choices will Drive Global Immigration

Perhaps no phenomenon in the last three decades has been as consequential yet overlooked as global migration. It has oiled the globalization machine that is reordering ever more of the world. This movement of people (immigration) is the third pillar of globalization, the other two being the movement of goods (trade) and the movement of money (finance). Even though immigrants represent a relatively small percentage of global population — there were 272 million immigrants in 2020 according to the UN, representing only 3.5% of the world population — their impact on the world economy has been very large. In 2018, immigrants remitted USD 689 billion to their home countries. This figure does not include unrecorded flows through formal or informal channels; the actual magnitude of global remittances is therefore likely larger.

This article argues that sub-replacement fertility rates of Western countries, social costs of illegal immigration, nationalist shift in global politics, falling per-capita incomes in the global South, population growth in Africa, and continued economic dysfunction of developing countries will lead to a backlash against unmanaged immigration of low-skilled workers. Industrialized countries will move to a regime of controlled immigration that will favor skilled or affluent immigrants who can make demonstrable contributions to their new country. At the same time, a number changes in the industrialized countries will encourage a reverse migration. These changes include higher taxes (necessitated by large sovereign debt burdens), rising income and wealth inequality, urban congestion, political polarization, acceptance of remote work, climate change, and an overall degradation in the quality of life for the upper classes.

RELATED ARTICLES

Since 1970, global migration flows have occurred primarily from the less developed countries (LDCs) to high-income countries (HICs) as shown in the figure below.

Economic and demographic factors have been the prime drivers of this movement — the high population growth in LICs during the last 70 years (see figure below) and their moribund economies created the pressure to immigrate.

Population growth rates are changing — demographic growth in Africa will be the primary source of increase in the world population while Asia will see a net decline and other regions will stay stable, as the figure below projects.

Western economies will see stable population even though their birth rates are projected to be significantly below replacement rate. This will occur because OECD countries are projected to experience significant increase in immigration — from 12% population share in 2010 to 17-19% in 2050 and 25-28% in 2100. Europe as a whole will see an even larger increase — from 15% in 2010 to 23-25% in 2050 and 36-39% in 2100. The United States continues its incoherent immigration policy and the number of undocumented immigrants in the country continues to climb. As of March 2020, the United States was confronting an unprecedented crisis on its southern border as thousands of migrants attempted to cross the border in anticipation of a more liberal immigration policy by the Biden administration.

This increase in the population share of immigrants will result in a profound change in the character, culture, and politics of the host countries and it will raise serious social and political challenges for them. If this influx is not managed, the arrival of a large number of poorly skilled immigrants will overwhelm the healthcare, social welfare, and education systems of the recipient countries. Political backlash and the resulting policy change will not allow this to happen. The obvious long-term management strategy — generating robust economic growth in the migrants’ countries of origin to reduce their reasons for immigration — is an unlikely prospect. The more likely scenario is that of modest economic growth in these countries; but mediocre growth creates its own paradox — middling per capita income growth in an underdeveloped country will keep most of its citizens poor enough to crave a better life elsewhere but make them rich enough that more of them can afford the journey abroad.

Thus far, barriers erected by wealthier nations have been unable to keep out economic migrants from the global South — typically poor, and often desperate — who come searching for work and a better life. On both sides of the Atlantic, the proposition that immigration poses a large-scale threat is gaining ground on the right (and in some cases, as well on the left) of the political spectrum. While the future of immigration policy is unclear in the USA as political stalemate between the Republicans and Democrats continues on this issue, other parts of the rich world — Europe, notably — are projected to experience more immigration than they have before, as persistently high fertility rates in Africa produce a demographic bulge of young people eager to make a better life across the Mediterranean (see figure below).

Around the world, nations are erecting physical as well as metaphoric walls against immigrants as the backlash begins in earnest. Even before the pandemic, Hungary fenced off its boundary with Serbia, part of more than 1,000 kilometers of border walls erected around the European Union states since 1990. India has built a fence along most of its 2,500-mile border with Bangladesh, whose people are among the most vulnerable in the world to sea-level rise. The United States, of course, has its own walls for immigrants — literal as well as figurative ones.

We are at the beginning of an era of significant change in the structure, composition, and magnitude of world migration flows. Rich, aging countries will continue to need workers as their working-age population will keep shrinking. People in poor countries will need jobs; continued rise in global inequality will mean that migrants will have ever fewer opportunities in their home countries and a lot to gain by moving abroad. Hence, the industrialized world will be forced to adopt harsh preventive strategies to stop the inflow of “undesirable” immigrants while encouraging immigration of “desirable” immigrants to fill its labor gaps.

Immigration policies will be the primary instruments of migrant selection, based on skill, wealth, or educational background of migrants. These will supplant the prior selection criteria that were based on national or “racial” origin and that dominated policymaking in the 1960s. Instruments such as points‐based systems, skill-selective policies, or occupational shortage lists will be used to manage the skill composition and the volume of skilled immigration into the country. Canada and Australia have already embarked on this path and other industrialized nations will soon follow.

Climate change is likely to be another driver of global immigration. Rising average temperatures are already pushing people from their homes to other nations in many middle-income countries. As warming continues in the coming decades, it will push people from agricultural areas to urban areas and from the global South to the richer global North. Should the flight away from hot climates reach the scale that current projections suggest is likely, it will amount to a vast redistribution of the world’s populations.

In some cases, this climate migration has already begun. In Southeast Asia, where nearly one-fourth of the global population lives, increasingly unpredictable monsoon rainfall and drought have made farming more difficult. The World Bank projects that this region will soon have the highest prevalence of food insecurity in the world. While some 8.5 million people have fled already — resettling mostly in the Persian Gulf — 17 million to 36 million more people may soon be uprooted, according to the World Bank. In the African Sahel, millions of rural people have been streaming toward the coasts and the cities amid drought and widespread crop failures; this trend will accelerate.

If it is not drought and crop failures that force large numbers of people to flee, it may be the rising seas. Climate scientists are projecting that the rising tides could result in the displacement of 150 million people globally. Projections show high tides subsuming much of Vietnam by 2050 — including most of the Mekong Delta, now home to 18 million people — as well as parts of China and Thailand, most of southern Iraq and nearly all of the Nile Delta, Egypt’s breadbasket. Many coastal regions of the United States are also at risk.

Rising temperatures will also make many parts of the world uninhabitable. By the end of the century, heat waves and humidity are projected to become so extreme in the tropics — currently one of the most densely populated regions of the world — that people without air-conditioning will simply die.

Current climate research provides a range of predictions about the scale of total global climate migration — from 50 million to 300 million people displaced. The industrialized countries will gird up for this tsunami by reinforcing selective immigration policies. At the same time, industrialized countries residents who live in regions affected by climate change, such as Florida, will seek greener (and dryer) pastures in other parts of the world.

All immigrants (in-migrants) to a destination country are also emigrants (out-migrants) from their home country. Yet the information about emigrants is often of poorer quality than that for the immigrants, even though, at the global level, they represent the same set of people. Emigrants contribute substantially to the economy of their home countries by sending back money, which is a good reason for these countries to track their emigrant population more effectively.

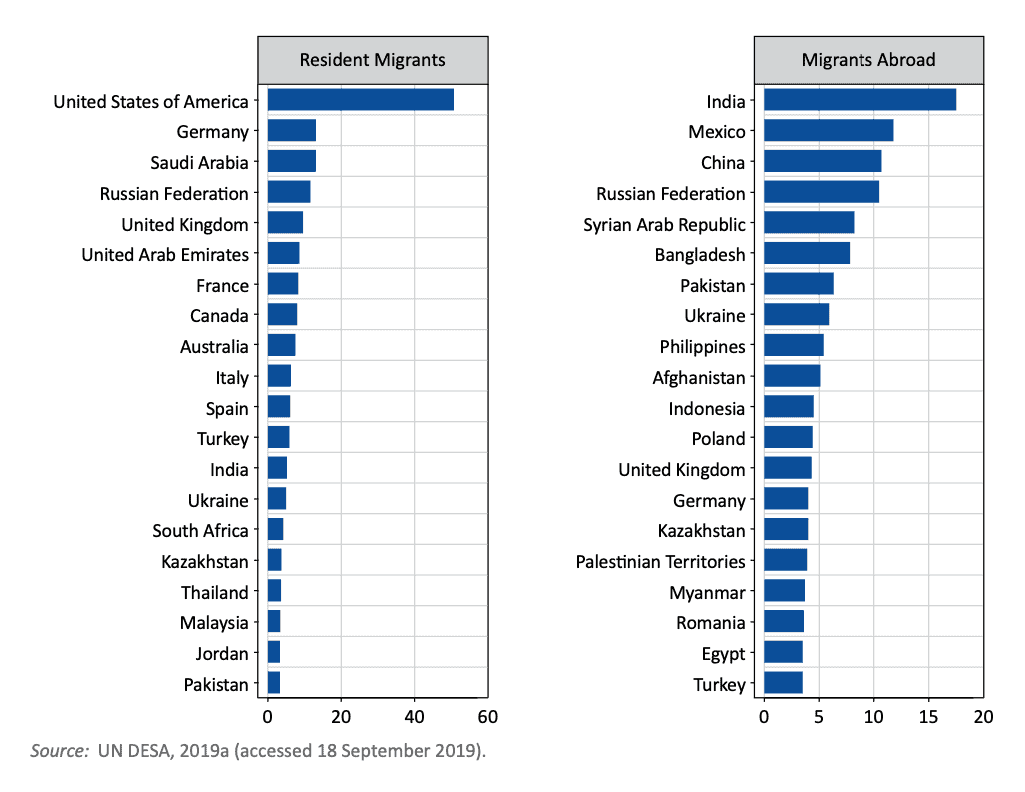

The countries ranked by number of immigrants (resident migrants) and emigrants (migrants abroad) as of 2019 are shown below.

The emigrants are coming primarily to high income countries. The figure above shows the most recent data about the countries that took in the most permanent residents – which includes foreign nationals moving to the country as well as those already there on a permanent basis. Clearly, the United States has been the country most welcoming of immigrants; since 1970 immigration has nearly doubled its population growth (see figure below). But the situation with other countries is different (please use the "Change country" feature in the figure below to see data for other countries).

India headed the list of countries ranked by emigrants for 2019, with nearly 16 million people born in the country who are living in another; Mexico comes in second with more than 12 million of its citizens living abroad, mainly in the United States.

As worldwide immigration moves to skill-selective policies, it will be dominated by a new set of players as described below:

- Skilled workers from developing countries who meet the selection criteria of industrialized countries.

- Digital nomads who can work remotely. They will move to countries with high quality of life and low cost of living.

- Investors who will use their financial assets to "buy" residency or citizenship to countries that can protect their financial assets, provide good opportunities for leisure travel, and provide a high quality of life.

- Retirees and semi-retirees from industrialized countries to escape congestion and political polarization in their home countries and to make their money run farther.

Here is how a recent immigrant from San Francisco to Kiev described his life before the move, “Rent was astronomical. Taxes were high. Your neighbors didn’t like you. I commuted an hour south to my job in Silicon Valley. I lived in a neighborhood with too much street crime, open drug use and $5 coffees. But it was worth it. Living in the epicenter of a boom that was changing the world was what mattered. But then COVID hit. Remote work offered a chance at living for a few months in towns where life felt easier. We decided to move to Kiev, my wife’s hometown, and now I do not want to live anywhere else.”

For a certain kind of worker, the pandemic presented an unexpected windfall. Many Americans were stuck, tied down by children or lost income or obligations to take care of the sick. But for those who were unencumbered, with jobs that could be performed from anywhere, it was a moment to grab the chance and improve their lifestyle. Their logic was simple: If you’re going to work from home indefinitely, why not make a new home in an exotic place? This cohort gathered their MacBooks, passports and N95 masks and became trendsetting digital nomads.

They lured more of their colleagues as they posted pictures of their workdays from empty beach resorts in Bali and took Zoom meetings supporting fresh tans. They made balcony offices at cheap Airbnbs in far off countries and booked state park campsites with Wi-Fi. They applied to those remote worker visa programs heavily advertised by Caribbean countries. This is a group that has tasted a better quality of life and they are not returning back to their old digs. In fact, their positive experience is a catalyst for others in their network to make the same move. This trend will only grow in the future.

Taking the digital nomad concept a step further are those who are towards the end of their career but do not believe that the quality of life they will enjoy in their home country will be satisfactory. They would rather live in a low-cost country while generating income through creative endeavors such as blogging about foreign cities, or vlogging about the food of different countries. With technology and online resources at one’s fingertips, and with similarly minded expatriates communicating and collaborating all over the world, living in a foreign land has never been easier for this group. Tools such as Google Voice for managing changing phone numbers, TransferWise and Xoom to move funds across countries, and video conferencing for intercontinental business meetings have made international remote work a reality. Thus, apart from the 20-30 year old age group, here are some other demographic groups that will consider moving to other countries in the future:

- Mobile Mid-lifers: If trekking abroad for long stretches was once considered the domain of the comfortably retired and the pre-professional (on their obligatory “Grand Tour”), the modern expat ecosystem has opened the door to everyone in between. The average age of members of InterNations — a community of expats founded in 2007 by two German entrepreneurs that now counts 3.7 million members in 168 countries — is 41, up from 38 in 2015.

- The Semi-Retirees: Couples or individuals who are past the child-rearing phase and have children who have moved out of their home are seeking adventure and novelty by moving abroad. These individuals are nearing retirement but have at least another one, two or possibly three life stages to go through.

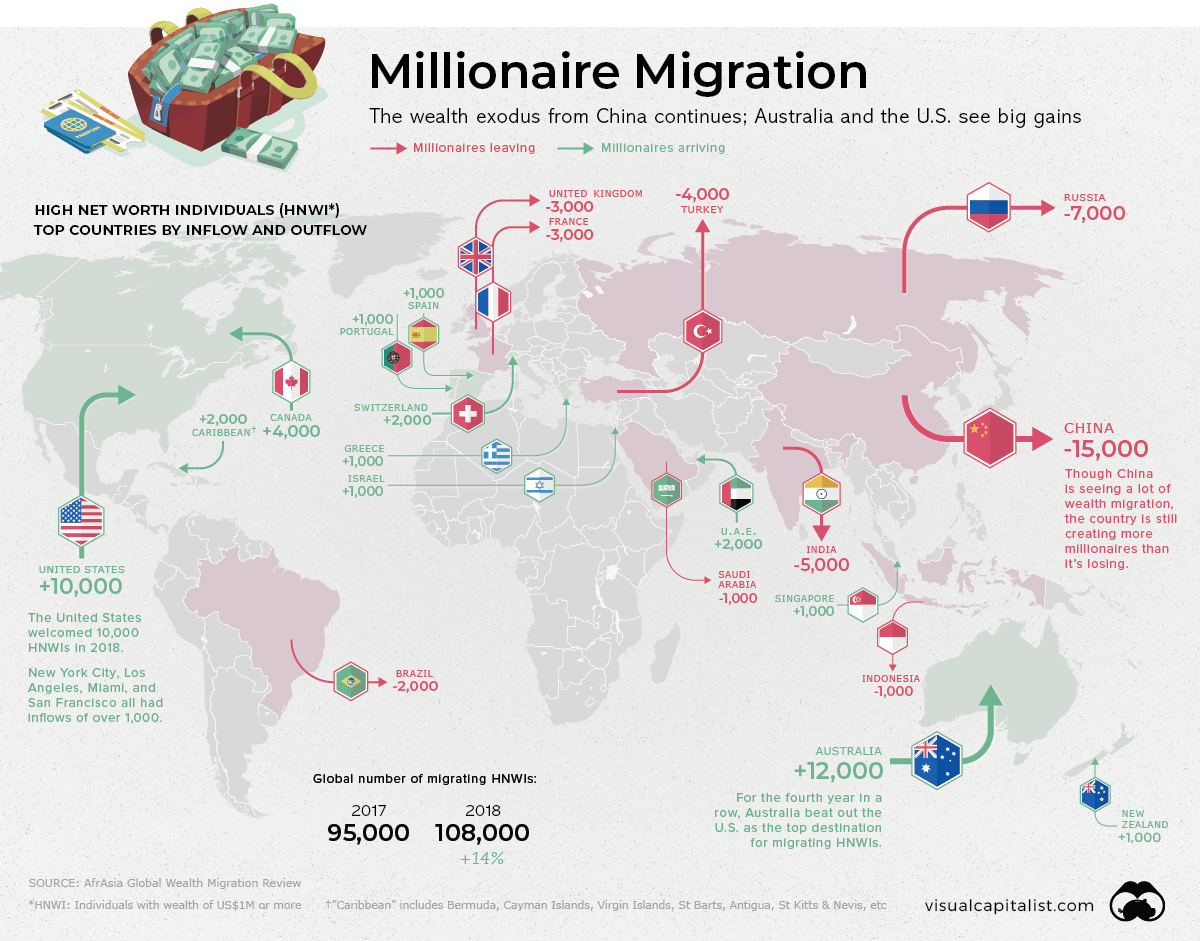

One group of immigrants is getting a red-carpet welcome around the world: millionaires. In 2018, a record 108,000 millionaires moved to another country. That’s still a small slice of the estimated 50 million millionaires around the world, defined as those having at least $1 million in assets (minus liabilities), not including their primary residence. This slice will grow in the future.

The growing contrast between migrants who are poor and those who are wealthy reveals a less-noticed form of global inequality, as well as an acceleration of a new culture of the rootless, borderless rich. The rich have always been a restless class, of course, moving with the seasons or the social circuit. But the current wave of millionaire migrations seems to have reached a new level, with wealthy families changing citizenship, sending their children overseas or moving permanently to the nation of their choice. This trend will grow in the coming decade.

The map of migration is also changing. Australia is now the world’s top destination for millionaires, beating the United States for the second straight year, according to New World Wealth. An estimated 12,000 millionaires moved to Australia in 2018, compared with the 10,000 who moved to the United States.

Indeed, taxes are not the primary reason why the wealthy migrate. In the past decades, the rich sought tax havens like Monaco, Switzerland or the Caymans to maximize their wealth. Now the rich — particularly from China, India and Russia — seek stable countries with financial systems that can protect their fortunes, even if income taxes are high.

As for countries that millionaires are fleeing, France tops the list, with 12,000 moving out during 2016. China ranked second, with 9,000, followed by Brazil, India, Latin America, and Turkey.

Personal safety goes hand in hand with education for many of the world’s millionaires when considering a move. Many millionaires from Latin America are seeking a haven from kidnapping and crime.

The flight of French wealth is driven by different worries. Millionaires leaving France cite religious tension and personal safety as their main reasons. While France’s high taxes on wealth are a factor, surveys reveal that social and political forces are more important.

Freedom of movement is an factor in where the rich will move. Advisory firms rank passports based on different factors, such as the mobility they afford their holders. For instance, Americans can travel easily to 87 countries. In 2019, that number was 171. “The drop of American passports over 50 percent in terms of mobility was a wake-up call for a lot of families,” said Armand Arton, the founder of Arton Capital. “The almighty U.S. passport is not as powerful as it used to be.”

Some other considerations that can influence the choice of where to move abroad are the following:

- Vetting Visas: Anyone who is moving abroad must check the visa requirements in their destination. The ease of obtaining a visa may dictate the destination decision.

- Health Care: Understand the requirements for health insurance in your destination country and your status in your country of origin. If you’re planning permanent residency, you may qualify for national coverage in your new country. Or you may continue or change insurance in your home country, as circumstances dictate.

- School Tests: If you are relocating with children, explore options for public local schools and private “international schools that cater to the needs of dual-culture families.

- Banking and Taxes: Set up as much banking online as possible for domestic fixed costs such as mortgages or other repayment loans. Set up local bank accounts for paying utilities and having cash on hand in your new home. You’ll may have to file taxes in your origin country for as long as you retain citizenship. If you plan to work in your new country, check the local tax requirements, based on earnings and origin of income.

- Staying Connected: For staying connected to family, friends and business back home, check with your phone carrier for international plans, particularly for restrictions on usage, or buy SIM cards in your inbound countries for local calling. For the long term, consider a separate foreign phone. Apps such as FaceTime and WhatsApp are cost-effective ways to stay in touch. Cloud services can be used not only for storing photos and music, but for health records and other important personal data you may need to access but don’t want to haul.

- Social Connections: Access to a friendly community in which it is easy to integrate can be an important consideration. For instance, in the US most elderly are confined to nursing homes with limited social interactions. A move to a South European country such as Greece or Italy can be an antidote to such isolation. Consider Dave Gallo who is leaving San Francisco. He plans to move to the town in north Italy from which his grandfather came to America. There is little traffic there, the cost of living is cheaper, it is surrounded by vineyards, and Mr. Gallo said he finds it easier to connect with people there. “The pandemic has created so much uncertainty that no one knows what life will be like for the next 10 to 15 years,” Mr. Gallo said. “For an old person, it’ll be even more difficult. Where do I want to spend the rest of my life?” For Mr. Gallo, the answer is Italy.

The pandemic has created so much uncertainty that no one knows what life will be like for the next 10 to 15 years.

At the same time, residents of the industrialized countries who can work remotely or who have accumulated ample financial resources will seek to move to other countries to escape the high taxes, urban congestion and the diminishing quality of life in the West.

The table below summarizes the key drivers for future immigration.

1

Countries with population growth rates below the replacement rate will seek skilled immigrants from developing countries.

2

Europe and USA will implement strict policies to stop or reduce the flow of undocumented immigrants who tax its infrastructure and welfare system

3

Remote working technology

The ability to work remotely will improve with innovations in technology. This will encourage the migration of skilled workers away from congested countries and urban areas.

4

Poor quality of life in western countries

High taxation, urban congestion, political discord will induce upper class residents of developed countries to seek retirement in other parts of the world with better quality of life